A connection with history

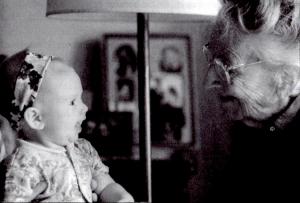

Edith Staton, whose grandfather was in Lincoln's cabinet, with her own great-granddaughter

Edith Staton, whose grandfather was in Lincoln's cabinet, with her own great-granddaughter

When I saw the Stephen Spielberg film about Abraham Lincoln the name of Montgomery Blair rang bells with me. He was a member of Lincoln’s cabinet who played a prominent role. I suddenly remember that I had written about Blair’s granddaughter whom I knew. So I am adding here what I wrote about her in my book All Her Paths Are Peace – Women Pioneers in Peacemaking. It is a little known anecdote from that period.

In 1993 Edith Staton was named as a consultant to a new committee for curing racial bias at her integrated Episcopal church in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The appointment would not be surprising but for the fact that she was then 97 years old. The position is a tribute not to her longevity but to her faithfulness in the task to trying to build a prejudice-free United States. She keeps on top of the news, eagerly questions visitors, and continues to work in the campaigns of those political candidates she supports. She got the residents in her apartment block into recycling before the city took it up. And when she was phoned early one morning to check a fact for this book, she was already out. In a church raffle she had offered her services to clean someone else’s silver, and that is what she was doing!

Edith is one of a growing number of American men and women who believe that an important step in curing racial bias is an honest conversation about the past. Through mutual forgiveness, those whose people suffered and those whose people may have been responsible for the suffering can find productive ways of working together. She identifies strongly and courageously with the latter group. She feels an urgency about healing the hurts of American history and she is a living link with that history.

Edith was born in Blair House in Washington, D.C .in 1896. Then the family home, it is now the official state guest house, and she was the last child born there. When she was still a small child the family moved to the Blair family farm in Silver Spring, Maryland, so named because her great grandfather, Francis Preston Blair discovered a spring in the woods while out riding.

Her grandfather, Montgomery Blair, was the lawyer who argued the famous Dred Scott case before the U.S. Supreme Court during 1856-57. Her grandfather lost the case for Scott’s freedom, but Edith is proud that he based his argument on the point that slaves were human beings and not property. Montgomery Blair became postmaster general in Abraham Lincoln’s cabinet.

During the Civil War one of Edith’s aunts, Mimma Blair Richey, was part of a riding party with the president just north of Washington when they found themselves too close to Confederate troops and had to take shelter in the only fort on the north side of the city, Fort Stevens. Southern general, Jubal Early, had brought his troops around north of Washington for a surprise attack. Aunt Minna remembered President Lincoln peeping out over the stockade to get a glimpse of the Confederates and a young aide pulling his coattails to keep him down. Years later, this incident was corroborated in the memoirs of that aide, Oliver Wendell Holmes.

The Confederate soldiers came across the Blair farm. The officers at one house found the whiskey, while the men at the other managed to set the home on fire with their campfires. Edith’s father, Mongomery Blair, Jr., used to say that it was the Blair whiskey that saved Washington.

The house was eventually rebuilt, and Edith’s family went there to live around the turn of the century. After the Fort Stevens battle, the body of a Confederate soldier was found near the spring and was buried by the woods with a small stone marker. “As children, we used to put violets on the grave every spring,” says Edith. She was one of seven children. They had a black maid, Dee, who also looked after the children. She had been born a slave in North Carolina. “We loved her,” says Edith. “She stayed with us until she died. But she never sat at table with us. She didn’t expect it, and neither did we.”

Edith says that only after she began to take time in quiet to seek direction was she able to have an honest conversation in her own spirit about the past and to face the depth of racial bias herself. ”I realized that as much as I loved (Dee), there was a difference; we never ate together. I have begun to see that I have an inborn racial prejudice that is deep-rooted. But I do believe that we can pray for forgiveness for all kinds of sin, and it does come. It’s like an alcoholic, until you admit that you have a racial bias, you can’t be helped to change.”

Edith’s husband was Adolphus Staton, a navy admiral who died in 1964. Her father-in-law had run away from home, a southern plantation, at the age of fifteen to join the Confederate army. Later in life he would say that he was glad that the South had lost, because slavery was terrible for the owners as well as the slaves. It fed a false pride and attitude of superiority which, says Edith, “has descended to the third and fourth generations.”

Such attitudes and low expectations of blacks are a source of deep regret for Edith. She is particularly concerned abut the legacy of slavery in terms of the needs of inner-city schools and what she regards as the selfishness of wealthy suburbs. “Integrating the schools has been an important step,” she says, “but the inner schools need equitable funding with suburban schools. The people who need things most, help with education and social services, get the least. This is wrong. We’re all responsible for the whole community. If you live in the suburbs you cannot ignore the plight of the inner city.”

Extract from All Her Paths Are Peace – Women Pioneers in Peacemaking

by Michael Henderson Kumarian Press 1994