The traitor and the knight

The most interesting of our Willcocks ancestors are possibly two brothers, one, Richard, who became Deputy Inspector General of the Royal Irish Constabulary and was knighted, and the other Joseph, who emigrated to Canada and deserted to the Americans in the war of 1812 and, if he had not been killed at the battle of Fort Erie would, according to a family historian, have been hanged. The one has been called the founder of modern policing, the other Canada’s Benedict Arnold, the worst traitor in Canadian history and the man who bears the greatest responsibility for the burning of Washington in 1814.

The most interesting of our Willcocks ancestors are possibly two brothers, one, Richard, who became Deputy Inspector General of the Royal Irish Constabulary and was knighted, and the other Joseph, who emigrated to Canada and deserted to the Americans in the war of 1812 and, if he had not been killed at the battle of Fort Erie would, according to a family historian, have been hanged. The one has been called the founder of modern policing, the other Canada’s Benedict Arnold, the worst traitor in Canadian history and the man who bears the greatest responsibility for the burning of Washington in 1814.

Sir Richard Henry Willcocks, first Inspector-General of the Munster Constabulary, was my great, great, great grandfather1. He was born 26 July 1768 and died 7 April 1834 and like many of the family was buried in the family plot at Chapelizod, near Dublin. He was married to Lucy Anne Irwin.

Sir Richard was employed from 1807 to 1827 in active service in different parts of Ireland. He was sent as a Stipendiary Magistrate, from time to time, into the Counties of Kerry, Limerick, Tipperary, Cork, Waterford, Kilkenny, Meath, and Westmeath; and, according to Baron Hatherton, Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (1833-4)2, ‘By his own exertions unaided by police, he successively tranquillized those counties.’ This, Hatherton writes, ‘was affected chiefly by obtaining private information, apprehending the principal offenders, bringing them to trial, securing witnesses, and preventing them from being tampered with.’

Writing in 1827, Hatherton notes Willcock’s role in the suppression of the Emmet conspiracy: ‘In 1803, he obtained and communicated to the Government the first information of Emmet’s designs, and thereby prevented the insurgents from gaining possession of Dublin. On that occasion he narrowly escaped assassination; eight persons having been stationed in different places for the purpose of attacking him. Immediately afterwards he organized a Yeomanry Corps in the County of Dublin, with the assistance of which he maintained the tranquillity of his own neighbourhood. He apprehended and committed to prison 35 persons concerned in Emmet’s insurrection.’3

A book published in 18534 puts flesh and blood on these sentences. It describes how he rose from his sickbed and escaped the assassination attempts and laboured to convince sceptical government officials that even Dublin Castle was threatened by the rebellion. ‘He was perfectly convinced that his information was not to be disregarded, and was determined at the expense of his life, to be himself the bearer of a message to the Castle, by which, if he did not produce conviction in the minds of others, he would, at least, satisfy his own conscience.’

The contemporary account concludes, ‘About the same hour Captain Wilcox began to retrace his steps home. He had not seen or heard anything of his family since the evening before, when he left them in the midst of treason, and surrounded by danger; and the reader may imagine with what trembling solicitude he approached the precincts of his residence, where his wife and children had been for so many hours defenceless and exposed, liable at any moment to fall victim to the sanguinary fury of the disappointed ruffians by whom he himself had been devoted to destruction. The quiet and soothing flow of the river, the balmy freshness of the breeze, and melodies poured from the emulous throats of the feathered tribe, who rendered the atmosphere vocal with living harmony, were all lost upon the anxious ear and the straining eye of the husband and the father, who at every step was fearful of encountering some sight or sound of woe, which might consign him for the remainder of his days to solitude and bereavement. But his mansion was unmolested. The hand of violence had not approached it. Instead of smouldering and blackened walls, such as he had pictured in his excited imagination, the sun was shining on its peacefulness and splendour; and his presence revived the fainting hearts of its forlorn and anguish-stricken inmates, who had almost given him up for lost, and who now felt, with deepest gratitude, the truth of that saying of the royal Psalmist, that “though heaviness endure for a night, joy cometh in the morning.”’

The contemporary account concludes, ‘About the same hour Captain Wilcox began to retrace his steps home. He had not seen or heard anything of his family since the evening before, when he left them in the midst of treason, and surrounded by danger; and the reader may imagine with what trembling solicitude he approached the precincts of his residence, where his wife and children had been for so many hours defenceless and exposed, liable at any moment to fall victim to the sanguinary fury of the disappointed ruffians by whom he himself had been devoted to destruction. The quiet and soothing flow of the river, the balmy freshness of the breeze, and melodies poured from the emulous throats of the feathered tribe, who rendered the atmosphere vocal with living harmony, were all lost upon the anxious ear and the straining eye of the husband and the father, who at every step was fearful of encountering some sight or sound of woe, which might consign him for the remainder of his days to solitude and bereavement. But his mansion was unmolested. The hand of violence had not approached it. Instead of smouldering and blackened walls, such as he had pictured in his excited imagination, the sun was shining on its peacefulness and splendour; and his presence revived the fainting hearts of its forlorn and anguish-stricken inmates, who had almost given him up for lost, and who now felt, with deepest gratitude, the truth of that saying of the royal Psalmist, that “though heaviness endure for a night, joy cometh in the morning.”’

Emmet was caught and tried and condemned to death. He was executed on 20 September 1803, his executioner displaying his head to the crowd and exclaiming, ‘This is the head of a traitor, Robert Emmet.’ His purported last words at his trial have gone into Irish history: ‘When my country takes her place among the victims of the earth, then, and not till then, let my epitaph be written.’ W.B.Yeats called him ‘the leading saint of Irish nationalism’.

In 1814 Sir Robert Peel, as Secretary for Ireland, introduced a bill in Parliament, the Peace Preservation Act. He appointed Richard Willcocks a Chief Magistrate to command the first detachment of the the PPF, Peace Preservation Force (the word ‘police’, being unpopular with the establishment, was not used), in the barony of Middlethird in County Tipperary where in the previous three years there had been a lawlessness connected with agrarian problems.5’ These, the first paid policemen in Ireland, were soon known particularly by nationalists as ‘Peelers’. In a life of Sir Robert Peel, author Norman Gash writes, ‘When Richard Willcocks was appointed a chief magistrate in September, even a political opponent like Lord Donoughmore was moved to congratulate the government on their obvious determination to exclude political considerations and make efficiency the sole test of appointments.’ And the Dublin Evening Post which opposed the Peace Preservation Act still praised Willcocks as ‘a meritorious and excellent magistrate’.

By the end of September Peel was able to write that the practical proof of the efficacy of the PPF was ‘that since the day on which Middlethird was proclaimed, I have not had the report of any outrage of any description either in that or in any other part of Tipperary, an extraordinary state of things in that county.’ Lord Whitworth, the Lord Lieutenant, reported, ‘Although the police bill has been but a very few weeks in operation, the effect is already such as to justify the most sanguine expectation of its ultimate success’. He pointed out that Tipperary had long been the worst of the counties, and that since this measure had been applied it was ‘in a state of perfect tranquillity’.

According to Professor Galen Broeker the PPF was turned into an ‘elite corps’ of outrage specialists: ‘By the end of October 1815 the Peace Preservation Force had proved itself to be of value in the struggle against agrarian crime. But one part of the Force in particular, the chief or stipendiary magistrate, had proved an outstanding success…One of the reasons for the early success of this office lies in the nature of Peel’s first two appointments, Willcocks and Wilson. The chief secretary’s insistence that ability rather than patronage or politics should determine the selection of the members of the Force proved sound, for both Willcocks and Wilson served the Irish government long and well. “Active, intelligent and useful”, Willcocks emerges as the key figure in the early history of the Force. Possibly it can be said that Willcocks was Ireland’s first truly professional police official. Apparently he avoided serious political involvement, his attitude toward the lower classes seems to have been free of the hatred and fear felt by numbers of the local magistrates, and by the standards of contemporary political morality he was honest. Whatever success the Force had at this time must be attributed to the initiative and leadership of Willcocks.’

In a letter to the Civil Undersecretary, William Gregory, at Dublin Castle (14 Dec. 1815) Willcocks himself wrote, “Magistrates of the highest respectability, catholic and protestant, are pledged, each to the other, and one and all, to support the laws, and bring to justice those who should offend against them.”’

‘By 1822,’ writes Jim Herlihy in The Royal Irish Constabulary ‘half the counties of Ireland had benefited from the use of the PPF.’ In Tipperary the success of the Force in ‘patrolling, detection and preparing evidence’ in Tipperary moved the Lord-Lieutenant, the Marquess of Wellesley, to state in May 1822 ‘It is impossible to bestow too much commendation on the exertions of the police under Major Willcocks.’

In 1825 Wellesley wrote to the Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool, ‘Every measure, insurrection act, police, tithe bill, revisions of magistracy, petty sessions, better administration of law, has succeeded beyond my most sanguine hopes. The general prosperity of the empire begins to reach Ireland. Prices have improved, rents and even tithes are better paid, and in the districts which had been better paid, and in the districts in which people had been most disturbed the people are turning their attention to pursuits of industry and honest labour, instead of plotting or executing schemes of outrage and violence.. In short I should have been able…to present the gratifying tribute of Ireland tranquillized to his majesty were not the general prosperity and happiness disturbed by the noisy fury of the Catholic Association…’

In January 1826 Willcocks, who by then had been for three years Inspector General of the Munster Constabulary, reported to Wellesley on the ‘exceptional peace’ in Munster and added that ‘what renders it still more gratifying is that the relinquishment of outrage has not been effects by coercive measures but gradually attained by legitimate causes.’

In 1827 he resigned because of ill-health. A reply to his resignation from Marquis Wellesley6, pays high tribute and adds that the lord-lieutenant ‘feels it to be a duty to provide adequately for the retirement of a respectable and deserving public servant’. Indeed, the success of Peel’s Peace Preservation Force has been credited7 to ‘the extensive work of Richard Willcocks’. Hatherton sums up, ‘It is universally allowed that there never was a more efficient Magistrate.’ He was knighted on retiring. Donal O’Sullivan, an authority on the Royal Irish Constabulary and the author of The Irish Constabularies, 1822-1922, wrote me, ‘It is likely that he received the recognition for his pioneering police work – which led to the establishment of the County Constabularies and which in turn was the basis for policing all over the world.’ He added that ‘Major Willcocks was in many ways the real pioneer of modern policing’.

In 1827 he resigned because of ill-health. A reply to his resignation from Marquis Wellesley6, pays high tribute and adds that the lord-lieutenant ‘feels it to be a duty to provide adequately for the retirement of a respectable and deserving public servant’. Indeed, the success of Peel’s Peace Preservation Force has been credited7 to ‘the extensive work of Richard Willcocks’. Hatherton sums up, ‘It is universally allowed that there never was a more efficient Magistrate.’ He was knighted on retiring. Donal O’Sullivan, an authority on the Royal Irish Constabulary and the author of The Irish Constabularies, 1822-1922, wrote me, ‘It is likely that he received the recognition for his pioneering police work – which led to the establishment of the County Constabularies and which in turn was the basis for policing all over the world.’ He added that ‘Major Willcocks was in many ways the real pioneer of modern policing’.

O’Sullivan writes that despite its successes, Peel’s PPF failed to find favour with the government and as time went by was equated with the military by the people who opposed its tactics. But it had fulfilled one positive achievement in that ‘it bridged the gap between the old baronial constabulary and watch systems and the establishment of a newer and more modern civil police forces, helping to break down the traditional, but the very inefficient magisterial system.’ County constabularies and city police forces were subsequently established in Great Britain and later extended throughout the British Commonwealth, all based on the Irish models.’

According to Professor Broeker ‘The Irish Constabulary exerted a major influence upon the development of the colonial peace forces of the British Empire’. And Sir Charles Jefferies writes in The Colonial Police that not only did the Constabulary serve as a model for many of the colonial forces of the last century, but also as long as the parent organization existed it was a major source of recruitment for the officers of these police systems8. In some instances the personnel of the colonial forces were trained at the Constabulary depots in Ireland, a service still provided in the mid-twentieth century by the Royal Ulster Constabulary.

According to Professor Broeker ‘The Irish Constabulary exerted a major influence upon the development of the colonial peace forces of the British Empire’. And Sir Charles Jefferies writes in The Colonial Police that not only did the Constabulary serve as a model for many of the colonial forces of the last century, but also as long as the parent organization existed it was a major source of recruitment for the officers of these police systems8. In some instances the personnel of the colonial forces were trained at the Constabulary depots in Ireland, a service still provided in the mid-twentieth century by the Royal Ulster Constabulary.

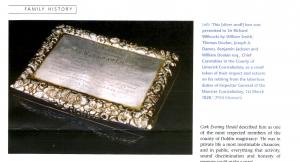

Willcocks’ death notice in the Cork Evening Herald of 9/4/1834 reads: ‘Sir Richard Willcocks, one of the oldest and most respected members of the county of Dublin magistracy died at his late Dublin residence, Palmerston, yesterday. He was many years inspector-general of constabulary and upon his retirement in 1827 he received the honour of Knighthood at the hands of the Marquess Wellesley as a well earned mark of approval for the zealous and efficient discharge of his onerous public duties. He was in private life a most inestimable character, and in public, everything that activity, sound discrimination and honesty of purpose could make a man.’ 9

|

(please click on the photograph to view the original)

Canada’s Benedict Arnold

The course in life of Richard’s brother, Joseph, ran rather differently. He left his home in Palmerston because the family was in some financial distress as a result of the Irish rebellion of 1798 and emigrated to Upper Canada in 1799. He went to York because he was promised land by his cousin William Willcocks, mentioned earlier. Joseph found employment with his cousin Peter Russell, who was then the highest ranking official in Upper Canada. The Lt.-Governor, John Graves Simcoe, had returned to England and left Russell in charge of affairs until the arrival of the next governor-general.

As Governor Simcoe’s successor as senior representative of the Crown, Russell’s contribution to the day-to-day administration of the government of Upper Canada was, according to Austin Seton Thompson10 , of a high order: ‘For three years as president and administrator he laboured in the difficult and perplexing days of early settlement and had more to do than anyone with the establishment of the operations of government on an orderly and efficient basis. He shares the distinction with Simcoe of having nurtured Toronto in its infancy and having set it on a firm course towards its destiny as a great metropolitan city.’

Joseph managed Russell’s farm and became his scribe. He also kept a diary and a letter book11 which has been described as “the best extant record of life in early Upper Canada’. When he was perceived as presuming above his station Russell fired him.

While trying to obtain some status in Canada Joseph had written his brother Richard asking for letters of reference. He wanted to impress on Simcoe that ‘my coming to the country was a matter of my own election and not any default in my conduct.’ For some reason, possibly a falling out with Richard’s wife, Lucy, the references were not forthcoming. One of the reasons Joseph had difficulty in Canada was because of the fact that a false rumour persisted that he had participated against the British in the rebellion. In one letter he affirms his ‘attachment to the King and Constitution and my zealous exertions to suppress the late Melancholy which pervaded my native country’.

John B. Lee, a Canadian poet and author, has made a study of Joseph’s life12 and read his many letters. He emailed me: ‘Joseph makes it clear that he had lead a life of drinking and sporting at home in Palmerston, and that he and his family were doomed to certain financial ruin if he remained. He sent a considerable sum of money to Ireland in order to pay off his own debts. He also makes a note of the fact that he witnessed a hanging in Canada of a man who forged a cheque and who was in debt.

‘Joseph does reveal himself as a scion of Anglo-Irish gentry. His debts are to tailors and bootmakers. He dresses the fine gentleman and has a cane made of oak with a fine brass monogrammed head. He buys a boat and learns to sail in the York harbour. He upsets a horse sled in the snow because of his love for speed. He suffers the side effects of a drug addiction from some medication he is taking due to pain from an injury. He is frequently drunk and drinks heavily with his fellow radicals. On one occasion he confesses that he was “drunk and perceived as such” by his employer. He loves good food, fine claret, fine clothing, and fishing, hunting, racing, shooting and boating.’

Peter Russell had enemies who found it in their interest to support Joseph. He was hired as clerk to the parliament and then was given the office of Sheriff of the Home District. He established the first political opposition the Upper Canadian or Freeman’s Journal. His politics becoming slowly radicalised by a series of events. His newspaper was rabidly anti the Governor-General Gore, though not anti-British. There were vitriolic assaults on Gore in its inaugural issue in 1807.

In the final issue of the Freemen’s Journal in he wrote, ‘I am flattered at being ranked among the enemies of the King’s servants in this colony. I glory in the distinction. Is it truth and a constant adherence to the interests of the country that has excited so much alarm among the band of sycophantic office hunters, pensioners and pimps.’ Joseph became, according to Guy Saunders, a past president of the York Pioneer and Historical Society, a ‘thorn in the flesh’ for the Government of Upper Canada. He soon found himself fired from his position and jailed for sedition. Gore called him ‘that seditious printer’. In the meantime he had been popularly elected to the Legislative Assembly where he served three terms (1808-1812).

When the war of 1812 broke out and General Brock prorogued parliament Willcocks found himself eyed with great suspicion by many who thought he had taken part against the British at home in Ireland in the rebellion of 1798. Gore suspected Willcocks of plotting to overthrow the government of Upper Canada and of conspiring with the exiled former head of United Irishmen, Thomas Addis Emmet, later attorney general of New York. Thomas was incidentally the older brother of the Emmet whose insurrection Richard had done much to thwart. One website, a People’s History of Canada, describes Joseph as ‘the leading critic of British military rule, who had been a troublemaker since the day he arrived from Ireland in 1799’. By the outbreak of the war he was ‘the uncontested leader of the unofficial opposition’.

Joseph led successful legislative efforts to block Major General Isaac Brock’s attempt to declare martial law in Upper Canada at the outbreak of the war, then suddenly reversed himself to become the right-hand man to Canada’s military commander. He was called upon by Brock to serve as emissary to the Grand River Mohawk and brought them into line with the British cause. In 1812 Willcocks served with distinction as a gentleman volunteer at the battle of Queenston Heights, a battle in which General Brock was killed.

Joseph fell out with Brock’s successor who moved to stiffen colonial resistance to the American threat by cracking down on Canadian dissidents. In 1813 Joseph began corresponding with the American Secretary of State, passing on information about British troop movements: ‘I do not hesitate to say that as soon as the British are driven out from amongst us I shall… with the assistance of my friends render this province independent of British influence.’

‘His politics evolved slowly and his abandonment of the British cause,’ Lee writes, ‘came at a very late date after considerable persecution and a complete lack of recognition of his contribution to Canada.’

In the late summer of 1813 Joseph defected to the United States Army at Fort George and raised a force of expatriate Canadians calling themselves the Canadian Volunteers. The Americans made him an officer with the rank of major, and then promoted him to lt.-colonel as he led this band of 150 Canadians, including some other members of the Legislature, against Canada.

In May 1814 fifteen Upper Canadians, including Willcocks, were charged with high treason. Eight were convicted and sentenced to hang13. They were hanged, drawn and quartered at Burlington Heights on 20 July and their heads were cut off and exhibited. Joseph Willcocks was tried and convicted in absentia. He kept on fighting for the Americans, his army of traitors making up part of America’s last invasion force under the command of General Winfield Scott.

The Americans had invaded in April, burned York and retreated to occupy Newark now called Niagara on the Lake. Willcocks offered his services to the invaders. Contemporary reports say he served bravely at the battle of Lundy’s Lane, the bloodiest battle of the war and indeed thought to be the bloodiest battle ever fought on North American soil prior to the civil war.

In 1814 Fort Erie was occupied by US forces under the command of Willcocks and the battle of Fort Erie involved a struggle by the British to drive American forces out of the fort. The US forces were roundly defeated and Willcocks was killed on September 4. There were no records kept of the enemy casualties and it not known until recently where he might be buried, as his body was not taken with the other officers14. The Montreal Herald reported (15 October) ‘It is officially announced by General Ripley (the American general) that the traitor Willcocks was killed in the sortie from Fort Erie on the 4th ult., greatly lamented by the general and his army.’

In 1814 Fort Erie was occupied by US forces under the command of Willcocks and the battle of Fort Erie involved a struggle by the British to drive American forces out of the fort. The US forces were roundly defeated and Willcocks was killed on September 4. There were no records kept of the enemy casualties and it not known until recently where he might be buried, as his body was not taken with the other officers14. The Montreal Herald reported (15 October) ‘It is officially announced by General Ripley (the American general) that the traitor Willcocks was killed in the sortie from Fort Erie on the 4th ult., greatly lamented by the general and his army.’

‘Vilified by Canadian history, championed as a hero by the United States,’ writes Lee, ‘he was summarily forgotten.’ Donald E. Graves, the Canadian military historian, describes him as ‘the worst traitor in Canadian history and the man who bears the greatest responsibility for the burning of Washington in 1814’15. He has also been called ‘Canada’s Benedict Arnold’. ‘It seems unfortunate,’ writes Saunders, ‘that Joseph, who could have gone far in the history of Upper Canada, should end his life as a traitor.’

Graves intends at some point to write a monograph about Joseph Willcocks but, as he told me, writing about a Canadian traitor does not rank high in his priorities. He had earlier written of Joseph, in his thesis on the Canadian Volunteers, that he never did anything that was not meant to further his own career. Lee disputes this and writes: ‘His politics evolved slowly and his abandonment of the British cause came at a very late date and only after considerable persecution and a complete lack of recognition of his contribution to Canada.’

Lee has devoted much time to probing Joseph’s character and writing about him and says that whatever the truth, he was a man who does not inspire moderate opinions. ‘Just as Benedict Arnold had his reasons for choosing sides, so too Joseph Willcock’s betrayal of his country was not without cause.’

The Dictionary of Canadian Biography records that Joseph Willcocks opposed arbitrary and distant power, valued loyalty to his country, rather than to its rulers, and believed in the independence of colonial legislatures. An earlier authority, Gourlay, in 1818 wrote of Willcocks’ predicament that ‘he could obtain neither favour nor mercy from the provincial government. At last, starving and exasperated he deserted to the enemy – after doing his devoirs like a man at the battle of Queenston Heights. Even this obtained for him neither complaisance nor immunity from abuse. He found himself ruined in fortune, opposed and hated by those in authority, without any prospect before him but starvation...in a moment of exasperation he deserted the ranks.’

Lee goes so far as to write, ‘Perhaps we have vilified the wrong brother. He (Richard) died a gentleman honoured by the Crown yet despised by the Irish people. This was his fate as the first son16 of Anglo-Irish gentry. He had never answered Joseph’s many letters home. Joseph Willcocks, second son, rests beneath the pavement in an unmarked grave at Fort Erie, Ontario. Let us honour the dead. Let us defy the liars and dignify his death by taking sides. Let us rescue even complicated stories from silence. Let us bring his face to the light17.’

An interesting proposition. Historian Graves, commenting on his different perspective, tells me, ‘You must remember that Lee is a poet and I am an historian; I work with facts, he works with feelings.’

Sir Richard Willcocks is buried in St Lawrence Church of Ireland cemetery. His epitaph reads: ‘Praises on tombs are trifles vainly spent; a man’s good name is his own monument.’

© Michael Henderson

1 Jim Herlihy, with whom I have corresponded about members of my family who served in the police over several generations, has written a short history and genealogical guide The Royal Irish Constabulary. He is a founder of the Garda Museum at Dublin Castle.

2 The Papers of Sir Edward John Littleton (1791-1863), 1st Baron Hatherton, Chief Secretary to the Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland, 1833-4 (Staffordshire Record Office D260/M/01/1086) give a thumbnail sketch of Sir Richard’s service

3 Willcocks testimony is in the National Archives in Dublin in the Rebellion Papers.

4 Remains of Rev. Samuel O’Sullivan, D.D.

5 The Irish Constabularies 1822-1922 by Donal J. O’Sullivan

6 Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland, brother of the Duke of Wellington and former Governor-General of India

7 Mr Secretary Peel – the Life of Robert Peel to 1830 by Norman Gash

8 In 1828 when it was necessary to improve the quality of policing in London Peel appointed two Irishmen as ‘commissioners’ of the Metropolitan Police. One of them, Richard Mayne (later Sir), is an ancestor of David Gore, husband of my wife’s first cousin.

9 We possess letters to Sir Richard from Robert Peel, when he was Chief Secretary in Ireland, from the Duke of Wellington and from one of Ireland’s greatest figures, Daniel O’Connell. In the museum of what is now the Police Service of Northern Ireland I was shown a silver snuff box presented to Sir Richard on his retirement by the chief constables in the County of Limerick ‘as a small token of their respect and esteem’.

10 In Spadina

11 The original letter book is in the possession of the National Library in Canada

12 Poems and an essay about him in his book In the Terrible Weather of Guns

13 Lee’s book Tongues of the Children tells something of the ‘treasons’ which led to the trial.

In 1847 a novel Victims of Tyranny by Charles Beardsley was published in Buffalo, New York. The central character of the novel was Sheriff Joseph Willcocks. Beardsley was the son of one of the lawyers who defended the accused.

14 In 1988, when excavating was done for a building in Fort Erie, a mass grave site was found of soldiers in US uniforms. Very likely, according to Lee, Joseph’s remains were among them. All were removed and returned to the US for reburial in a Military Cemetery with full honours. Patrick Kavanagh of the Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo told me in 2012 that the bodies were first buried in the Franklin Square Cemetery in Fort Erie and have since been reburied at Forest Lawn. He sent me a photograph of the monument, with no names on it, that marks the spot.

15 Lee says this is an exaggeration: ‘Willcocks led the burning party at Newark. But the parliament buildings at York were burned in April, four months prior to Willcock’s defection. The burning of Black Rock, and eventually Washington, were retaliations for the burning of Newark and St. David’s but more symbolically significant, the burning of the American capital was a direct response to the burning of York and the parliament at York, in which Willcocks was not involved at all.’

16 He was actually the second, and Joseph the third.

17 Lee emailed me: ‘When I was doing research on Traitor Willcocks, I was surprised how quickly everyone involved was willing to leap into the superlative condemnations and vilification of a man caught up in historical forces beyond his control. How explain the fact that he was “popularly" elected three times. That he was in the company of several other popularly elected representatives who were also members of the Canadian Volunteers. It is interesting to note that his fellow radicals returned to Ireland to present their case against Gore, and that the very man to whom they were required to present their case, a man named Casterleigh, was the man who appointed Gore in the first place. The names cross and criss-cross. the power struggle was very real indeed. Some believed in reform. Some resorted to reform by violence. Taking up arms brings about an easy solution. Capture and hang the traitor. It's interesting to quote, ''Treason is a mere matter of dates." Treasonist William Lyon Mackenzie fled, and then returned to become mayor of Toronto. Charles Duncombe escaped with his life and never returned. He became a legislator in his chosen state, California. When I was in the early days of my research and I asked a curator of a museum in Niagara on the Lake about Joseph Willcocks, he almost leapt the desk and gripped me by the throat for my presumption. "What the hell are you doing looking into the life of that traitor?"’